beverly hills HISTORY IN PICTURES AND PROSE

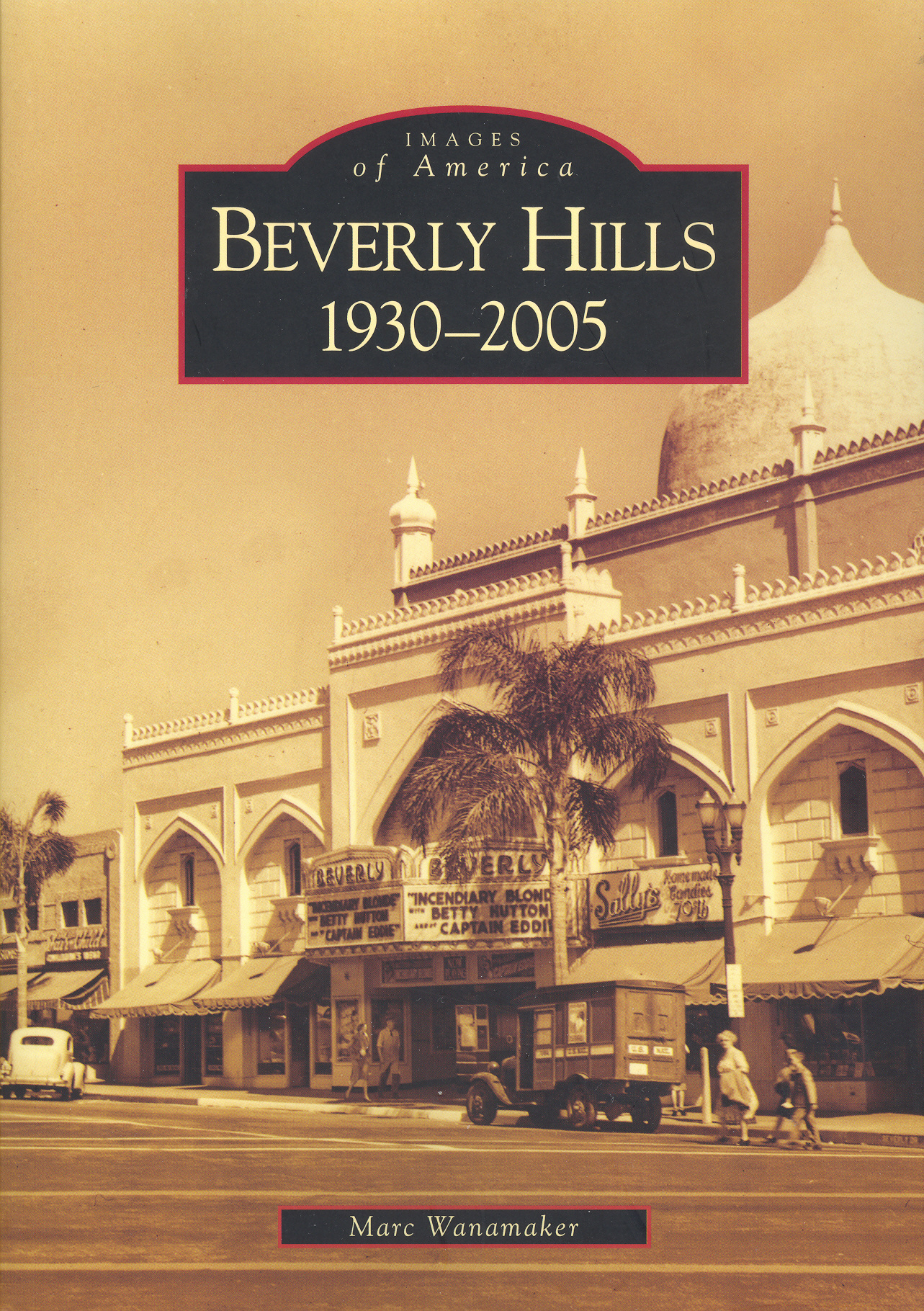

We recommend these books by our members, Robert S. Anderson and Marc Wanamaker. The wonderful historic photos above and many others can be found there. Purchase by clicking on the images.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BEVERLY HILLS

Throughout history, there appears to have always been something special about the land that became Beverly Hills. The original inhabitants, the native Tongva, recognized it as a kind of oasis in a semi-arid basin, the place they poetically called the gathering of the waters. The Spanish explorer Don Jose Gaspar de Portolà realized it too, and when his expedition happened upon the Tongva's Eden, he translated the name for it into Spanish as El Rodeo de las Aguas.

The Tongva native atop the Electric Fountain at the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica Boulevards.

With Europeans, however, came a series of difficulties, beginning with smallpox, which wiped out the majority of Tongva. In 1838, the governor of the Mexican-controlled California territory deeded the 4,500 acres that constitute the core of present-day Beverly Hills to Maria Rita Valdez Villa, the African-Mexican widow of a Spanish soldier. She started a cattle and horse ranch and built an adobe home at what is now the intersection of Alpine Drive and Sunset Boulevard. As was the custom, livestock grazed wherever they liked but were annually herded to a rodeo located near today's intersection of Pico and Robertson Boulevards.

In 1852, Maria Rita survived a siege and shoot-out with Native Americans who attacked her rancho. This may have influenced her to sell her land two years later to Henry Hancock and Benjamin Wilson. Unfortunately for the new owners, the waters dried up a few years later, followed by a long drought that left their livestock to die. Hancock and Wilson are remembered today for the upscale Hancock Park neighborhood and local geographic landmark Mount Wilson. By 1868, the land was owned by Edward Preuss who sought to establish a community for immigrant German farmers to be called Santa Maria. In the meantime, he turned the ranch into lima bean fields, selling his crop to cover taxes. Santa Maria was never to be after yet another drought thwarted Preuss' dream.

Early in the 1880s, Henry Hammel and Charles Denker acquired the land with the intention of creating Morocco, a subdivision with a North African theme. The U.S. economic collapse of 1888 put a quick end to that scheme. In 1900, the fortunes of the former rancho began to improve. A group of oil-speculating investors, led by Burton E. Green, bought the bean field on behalf of the Amalgamated Oil Company. Green drilled a series of wells that failed to strike oil; however, they did strike a lot of water -- enough to support a town. In 1906, Green and his partners reorganized as the Rodeo Land and Water Company. Inspired by Beverly Farms, Massachusetts, Green and his wife renamed the bean field Beverly Hills.

In 1907, landscape architect Wilbur D. Cook was hired to design a street plan for Beverly Hills. Cook laid out curving streets with larger lots on the north side, smaller lots on the south side, and a triangular commercial district between them. All the streets were tree-lined and land was set aside for public parks, four elementary schools, and a high school. The vision was to make the area affordable to a range of incomes, as long as the buyers weren’t Black or Jewish. These shameful restrictive covenants would eventually fall in the 1940s thanks to a lawsuit brought by Hattie McDaniel, Ethel Waters, and other notable African-Americans.

The first house was completed in 1907, but sales were slow. In 1912, to bolster the interest of potential buyers, Green completed construction of the Beverly Hills Hotel on the site where the waters once gathered. The luxurious establishment served not only travelers but the locals as a de facto city hall, community center, movie theatre, and religious worship venue. Sitting in what was then the middle of nowhere, the hotel was reached by the specially-constructed Dinky Railroad, a wondrous attraction in itself.

By 1914, the local population was large enough to support the incorporation of Beverly Hills as a city, but real growth didn’t take off until the era’s most glamorous Hollywood couple, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, bought a lot on Summit Drive and dubbed their home Pickfair. Following their fashionable lead was a host of film industry stars, directors, and producers who began the celebrity mystique that remains a constant of Beverly Hills to this day.

What also brought fame to the young city was the addition in 1919 of the Los Angeles Speedway, the site of auto races second in importance only to Indy. The course, covering most of the southwest quadrant of the city, barely made it through half of the Roaring Twenties. Among the notable structures built on land formerly traversed by race cars was the Beverly Wilshire Hotel in 1928. The same year, Edward L. Doheny completed Greystone, a 55-room mansion and estate, a wedding gift for his son, which is now owned by the City and operated as a museum, park, and event venue.

With growth came the return of a problem that haunted the 19th-century rancho, a potential shortage of water. In 1923, an effort to secure a steady water supply through annexation by the City of Los Angeles was defeated by the voters thanks to opposition led by Mary Pickford, who feared the loss of local identity. Celebrities continued to be important to civic life, most notably the nationally-cherished humorist and honorary mayor of Beverly Hills, Will Rogers. In his memory, the park across Sunset Boulevard from the Beverly Hills Hotel was renamed after his death.

The 1930s brought construction of the main post office and the magnificent Beverly Hills City Hall designed by architect William Gage in the Spanish Renaissance style. The old Santa Monica Park was expanded from three blocks to the entire length of the north side of Santa Monica Boulevard from Wilshire Boulevard to North Doheny Drive and renamed Beverly Gardens Park. The elegant Electric Fountain, featuring a central pillar atop which is posed a kneeling Tongva native amidst the spray of the “gathering waters,” was installed at the northeast corner of Wilshire and Santa Monica Boulevards. The jets of water effuse a multi-colored glow at night thanks to a programmed lighting system.

In the late 1940s, as the nation entered the post-World War II recovery, the City began to develop rapidly. With Rodeo Drive as its focus, the commercial district came to be called the Golden Triangle as an ever-increasing number of internationally-renowned retailers opened there. By the 1960s, the City’s reputation as a haven for the famous and center of grand homes, luxury shopping, and fine dining spread worldwide through films and TV shows shot or set there. The City also grew physically with the annexation of a large tract of land in the hills above the east side of town, the area known as Trousdale Estates, originally part of the Greystone estate.

Facing stiff competition for shoppers from new nearby shopping malls, Beverly Hills moved to shore up its status as the region’s premier shopping area. In 1989, Two Rodeo and its pedestrian path, Via Rodeo, opened, quickly becoming not only a shopping and tourist magnet but a popular photo and film backdrop. By the 1990s, the demand for services and the need for seismic retrofitting moved the city to restore and strengthen City Hall and build an expanded Civic Center with a modernized main fire station and library and an entirely new police headquarters.

In 1996, the Paley Center for Media opened its West Coast location, a significant new building by architect Richard Meier at the southwest corner of North Beverly Drive and South Santa Monica Boulevard. In addition, the shopping blocks of North Rodeo Drive were enhanced with new landscaped medians and sidewalks, as well as improved street lighting. Similar sidewalk and lighting enhancements were made to the shopping streets of North Beverly Drive and North Cañon Drive.

Moving into the 21st Century, the city added two new important attractions; the 9/11 Memorial, a striking design containing an actual steel beam recovered from the ruins of the World Trade Center, and the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, a significant cultural resource that repurposes the classic U.S. Post Office building. The grand hall of the old post office is now the Annenberg lobby with its enduring ceiling murals by artist Charles Kassler, Jr., a product of the WPA during the Great Depression. What was once the work area behind the postal clerks’ windows has been turned into a flexible 150-seat theatre, a theatre school with three classrooms, a café, and gift shop. A modern addition, the 500-seat Goldsmith Theatre, is a state-of-the-art-facility for presenting a wide range of world-class performers.

As Beverly Hills approached the 100th anniversary of its incorporation, concern began to grow over the lack of an historical preservation ordinance to protect significant structures located within the city limits. In response, the City Council enacted one with the honor of Historic Landmark No. 1 being bestowed upon the Beverly Hills Hotel. Since its centennial in 2014, Beverly Hills has continued to mature with renewed appreciation for its past, remaining true to Burton Green’s vision of an oasis of refinement, while meeting the challenges of the future.